Unless you remember television in the 1990s, you probably don't know the character of J. (Jacobo) Peterman, one of the most outrageous characters ever to appear on Seinfeld, a show in which literally every character was outrageous, extreme, and often unbelievable. "

"J. Peterman," in Seinfeld, was the owner of a company that sold items imported from the Third World, each highlighted in a a print catalog (this was before "e-commerce") that paired each item with a multi-paragraph memoir from Peterman himself, relating the events of some fantastic foreign travels he had been upon when he discovered a particular item that his company had begun importing to the United States.

To explain, here are some examples from the show:

Then in the distance I heard the bulls. I began running as fast as I could. Fortunately I was wearing my Italian cap-toe oxfords. Sophisticated yet different; nothing to make a huge fuss about. Rich dark brown calfskin leather. Matching leather vent. Men's whole and half sizes 7 through 13. Price $135.00.

And there, tucked into the river's bend was the object of my search. The Gwon-Jaya River market; fabrics and spices traded under a starlit sky. It was there that I discovered the Pamplona beret. Sizes seven-and-a-half through eight-and-three-quarters. Price? $35.00.In other words, the appeal of the wares of "J. Peterman" was romantic fantasy; a whiff of exciting adventure you could possess as soon as the UPS shipment could reach you.

However, if the imaginary character of "J. Peterman" was not amazing enough, you might be even more surprised to know that there was a "J. Peterman" catalog before there was a "J. Peterman" character on Seinfeld. The writers had lifted the story of a real person living an unbelievable life to create an imaginary person living a life no more improbable. Thank goodness for the First Amendment right of parody!

Moreover, even though the Seinfeld show -- the world's most successful "show about nothing" -- left the airwaves in 1998, the "J. Peterman Catalog" remains an institution. In a particularly Seinfeld-like touch, the actor who played "J. Peterman" for four years, John O'Hurley, serves on the board alongside of the real J. Peterman!

The cynical Elaine Benes in me sees personal blogging for marketing the way I see the J. Peterman catalog. Tying an experience to a product doesn't make the product more authentic; it changes the anecdote from genuine to crass. Moreover, when spend my money, I want it to spend it to have some of my own experiences -- like the experience of wearing a new dress and shoes at a party -- rather than vicariously sharing an experience with someone else. Moreover, mererly reading the J. Peterman catalog is all the vicarious experience I need.

Setting aside my personal insightfs, no one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the average American. I suppose that the price for having the freedom of someone like J. Peterman is slavery in the same cynical enterprise. Thus is my explanation for "how adding human interest to a post can appeal to peoples emotions because it describes personal experiences."

Moreover, the J. Peterman story suggests that anything sold "B-to-C", i.e., business to the consumer, can be marketed with human interest stories. Clothing is an obvious choice for anecdotal-based marketing, because any article of clothing -- from a plaid flannel shirt to a white linen jacket -- carries historical, geographical, and cultural associations. Furniture is another such item, although one that is less disposable.

However, even a product as prosaic as plain white flour -- the sort suitable for making cakes, pies, and bread -- has been marketed according to it cultural allusions for at least 100 years. For example, in the hardscrabble 1930s, one W. "Pappy" O'Daniel connected the "Hillbilly Flour" brand to rural home life by sponsoring a weekly country music radio program, featuring "The Light Crust Doughboys," that opened with a voice saying, "Pass the Biscuits, Pappy!" Meanwhile, up in Minneapolis, the Washburn-Crosby flour concern (later, "General Mills") invented a fictional "Betty Crocker" to first answer questions from homemakers about baking, and later to grace the boxes of the company's products.

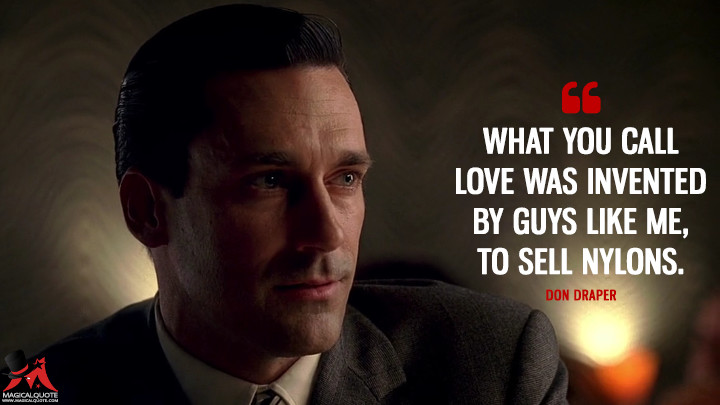

In fact, the marketing of flour with associations to home, kitchen, and families, serves as a classic example of "selling to the need" of the customer, rather than selling the product itself. In the hands of "an ad man," a five-pound bag of flour is a sack filled with possibilities, and redolent of memories. A package of nylon stockings promises the love of a handsome man. And a pair of shoes symbolizes the hearty masculinity of a young man testing his courage against certain death.

No comments:

Post a Comment